How did Memorial Day start? By an act of love and unity.

How did Memorial Day start? By an act of love and unity.

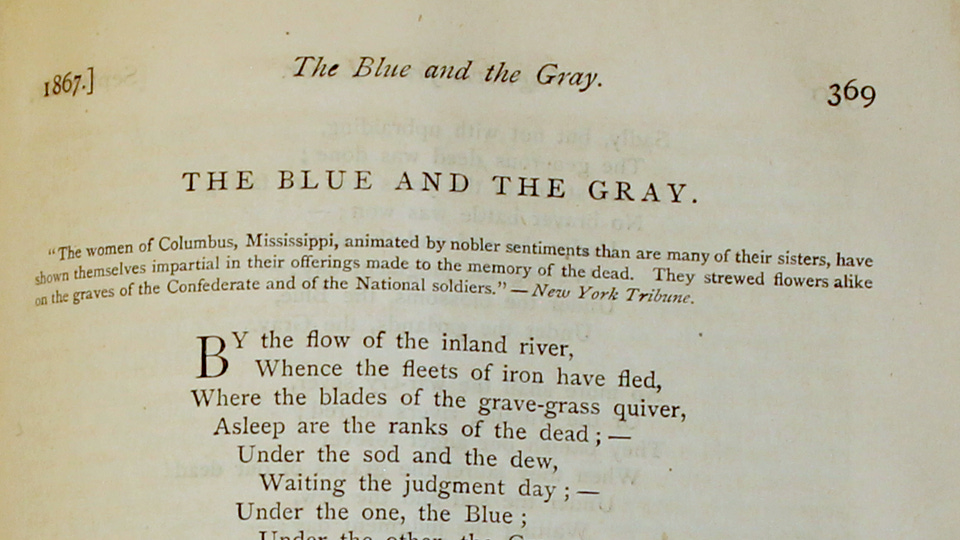

After the Civil War ended, in 1866, four women from Columbus, Mississippi put flowers on the graves of both Confederate and Union soldiers, an act of generosity that inspired the poem by Francis Miles Finch, "The Blue and the Gray," published in 1867 in the Atlantic Monthly.

They decided to honor the graves of the Union soldiers as well and sent notes of condolence to the northern soldiers' families. Based on this act of commemoration and conciliation, Columbus, Mississippi considers itself (as do several other cities in America) as the originator of Memorial Day.

Southern women had always decorated the graves of Confederate soldiers even before the end of the Civil War.

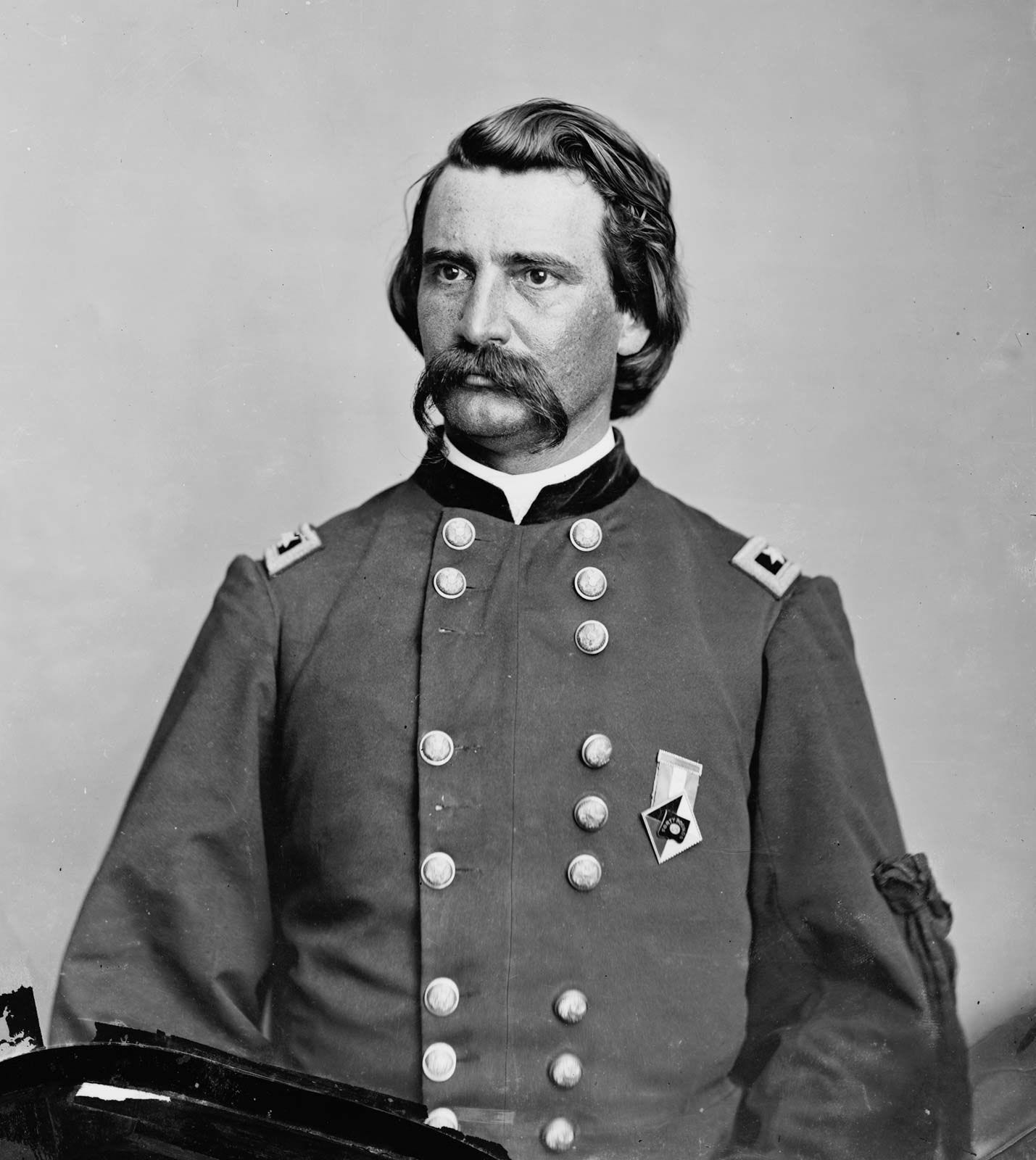

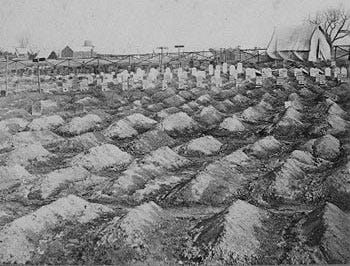

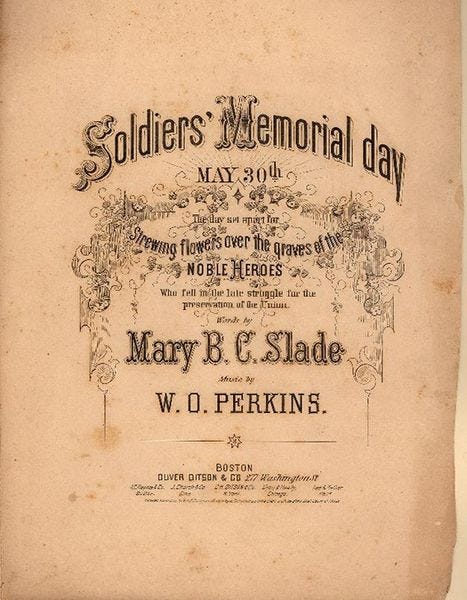

In 1868, Commander in Chief John A. Logan of the grand Army of the Republic, issued what was called General Order Number 11, designating May 30 as a memorial day. He declared it to be "for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet churchyard in the land."

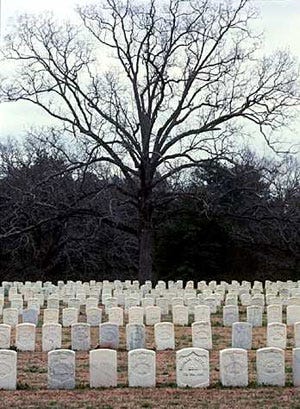

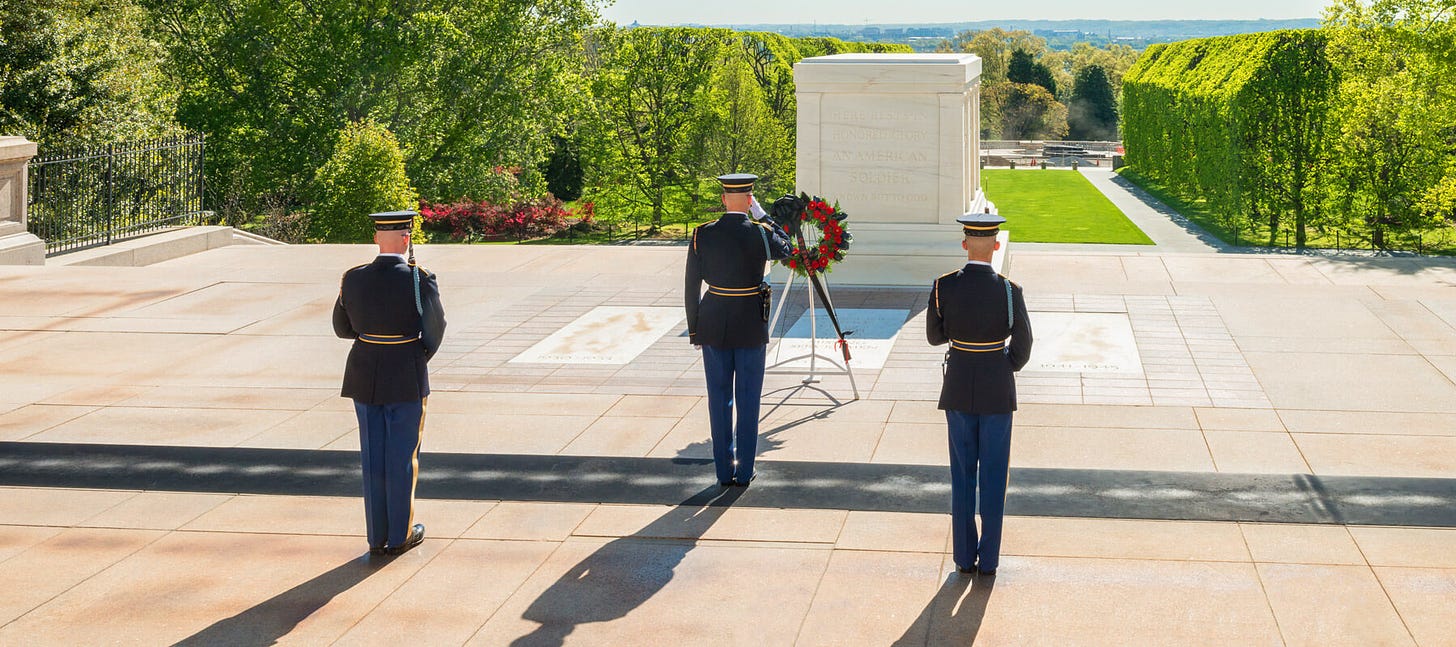

The first official national celebration of Memorial Day (originally Decoration Day) took place May 30, 1868, at Arlington National Cemetery.

Hailed as a national classic from the moment of its publication in 1867, Finch's poem entitled "The Blue and The Gray" is perhaps the most touching and expressive of all the "reconciliation poems" written after the War's end.

Finch explained what inspired him to write it:

“It struck me that the South was holding out a friendly hand, and that it was our duty, not only as conquerors, but as men and their fellow citizens of the nation, to grasp it.”

He was inspired by the following brief news item, which appeared in the New York Tribune:

"The women of Columbus, Mississippi, animated by nobler sentiments than many of their sisters, have shown themselves impartial in their offerings made to the memory of the dead. They strewed flowers alike on the graves of the Confederate and of the National soldiers."

Finch’s poem seemed to extend a full pardon to the South: “They banish our anger forever when they laurel the graves of our dead” was one of the lines.

Almost immediately, the poem circulated across America in books, magazines and newspapers. By the end of the 19th century, school children everywhere were required to memorize Finch’s poem.

It was not long before northerners decided that they would not only adopt the southern custom of Memorial Day, but also the southern custom of “burying the hatchet.”

A group of Union veterans explained their intentions in a letter to the Philadelphia Evening Telegraph on May 28, 1869:

“Wishing to bury forever the harsh feelings engendered by the war, Post 19 has decided not to pass by the graves of the Confederates sleeping in our lines, but divide each year between the blue and the grey the first floral offerings of a common country. We have no powerless foes. Post 19 thinks of the Southern dead only as brave men.”

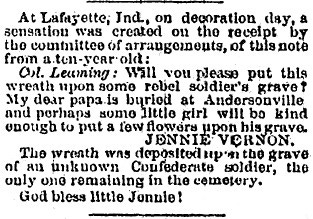

A 10-year-old girl from the North, Jennie Vernon, made a wreath of flowers and sent it to Colonel Leaming, in Lafayette, Ind., with the following note attached, published in The New Hampshire Patriot on July 15, 1868:

“Will you please put this wreath upon some rebel soldier’s grave? My dear papa is buried at Andersonville, Georgia and perhaps some little girl will be kind enough to put a few flowers upon his grave.”

The wreath she provided was placed on a grave in the cemetery, and the story of her kind gesture was reprinted throughout the nation that summer.

Jennie Vernon was the daughter of Sergeant Samuel James Walker Vernon, Company K of the 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry. Sgt. Vernon was captured on October 17, 1863 carrying dispatches to General Sherman. He died on June 24, 1864 at the Camp Sumter military prison near Andersonville, Georgia. Sgt. Vernon is buried in Andersonville National Cemetery, in Section K, grave number 2428, in what is now Andersonville National Historic Site.

The Blue And The Gray

By the flow of the inland river,

Whence the fleets of iron have fled,

Where the blades of the grave-grass quiver,

Asleep are the ranks of the dead:

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the judgment-day;

Under the one, the Blue,

Under the other, the Gray.

These in the robings of glory,

Those in the gloom of defeat,

All with the battle-blood gory,

In the dusk of eternity meet:

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the judgment-day,

Under the laurel, the Blue,

Under the willow, the Gray.

From the silence of sorrowful hours

The desolate mourners go,

Lovingly laden with flowers

Alike for the friend and the foe:

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the judgment-day,

Under the roses, the Blue,

Under the lilies, the Gray.

So, with an equal splendor,

The morning sun-rays fall,

With a touch impartially tender,

On the blossoms blooming for all:

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the judgment-day,

Broidered with gold, the Blue,

Mellowed with gold, the Gray.

So, when the summer calleth,

On forest and field of grain,

With an equal murmur falleth

The cooling drip of the rain:

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the judgment-day,

Wet with the rain, the Blue,

Wet with the rain, the Gray.

Sadly, but not with upbraiding,

The generous deed was done,

In the storm of the years that are fading

No braver battle was won:

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the judgment-day,

Under the blossoms, the Blue,

Under the garlands, the Gray.

No more shall the war cry sever,

Or the winding rivers be red;

They banish our anger forever

When they laurel the graves of our dead!

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the judgment-day,

Love and tears for the Blue,

Tears and love for the Gray.

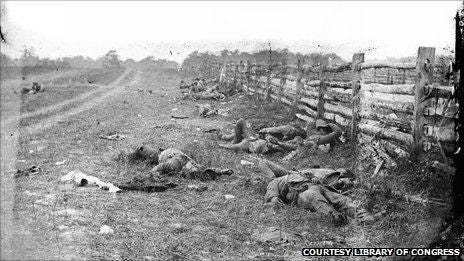

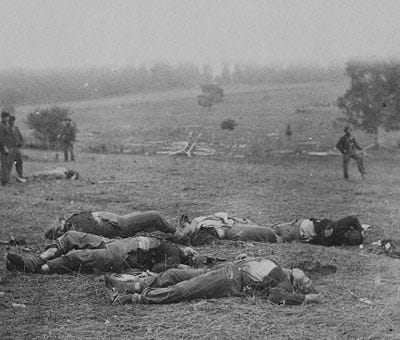

600,000 plus American soldiers died in the Civil War. Another million were wounded. Hundreds of thousands more died of disease & starvation. That's the equivalent of 8 MILLION today - the size of New York City.

The national observance of Memorial Day still takes place at Arlington today, with the placing of a wreath on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and the decoration of each grave with a small American flag. In 1971, federal law changed the observance of the holiday to the last Monday in May and extended it to honor all those who died in American wars.

“Today, we honor the heroes we have lost. We pray for the loved ones they left behind, and with God as our witness, we solemnly vow to protect, preserve and cherish this land they gave their last breath to defend.”